What Causes Hydrocephalus?

There are two general classifications of hydrocephalus, obstructive hydrocephalus and communicating hydrocephalus. Obstructive hydrocephalus arises when the pathways for CSF circulation are blocked but the reabsortion channels are open. This blockage can result from congenital anatomic abnormalities, or from brain tumors that choke off the normal paths for CSF circulation as they grow. Communicating hydrocephalus arises when the reabsoption mechanism becomes blocked but the pathways for CSF circulation are open. Any disease process that releases protein and debris into the CSF can result in communicating hydrocephalus. Brain hemorrhages, brain tumors, as even infectious or inflammatory conditions can lead to the release of debris into the CSF. This debris blocks the normal channels of reabsorption with a resultant build-up of fluid in the brain. The production of too much CSF is usually caused by a rare brain tumor called a choroid plexus papilloma.

How Is Hydrocephalus Diagnosed?

Hydrocephalus can lead to increased pressure inside the skull. This elevated intracranial pressure can result in headache, nausea, vomiting, lethargy, loss of vision, and even eye movement problems. In young children with unfused skulls, their head size may increase at an unusual rate. Once hydrocephalus is suspected, the diagnosis is confirmed with a CT or MRI scan of the brain.

How Is Hydrocephalus Treated?

Almost all forms of symptomatic hydrocephalus are treated with surgery. With obstructive hydrocephalus the goal of surgery is to relieve the blockage. If the blockage is due to an enlarging mass in the brain (such as a tumor, infection, or blood clot) removal of this mass may reopen the normal pathways for CSF circulation. In some forms of obstructive hydrocephalus a “third ventriculostomy” may be performed to bypass the blockage. Patients with communicating hydrocephalus and some patients with obstructive hydrocephalus are treated by implanting a shunt. A shunt is an implanted device that diverts the CSF from the brain to distant location in the body where it can be reabsorbed. The place into which the CSF is diverted is usually the peritoneal cavity (the area surrounding the abdominal organs). Rarely a shunt may divert the CSF to the chest, heart, or even the gall bladder.

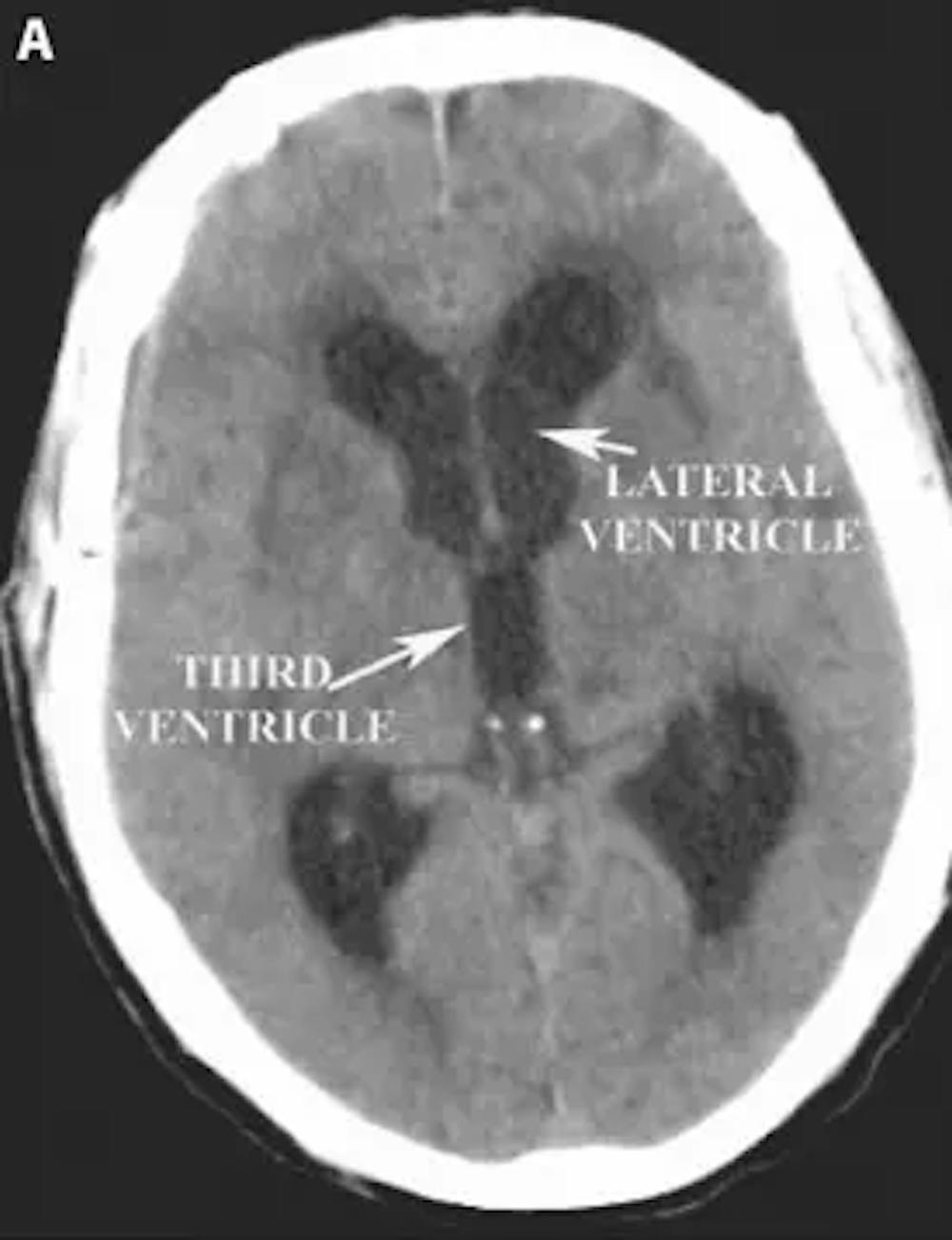

A) Pre-operative axial head CT scan demonstrating enlarged ventricles.

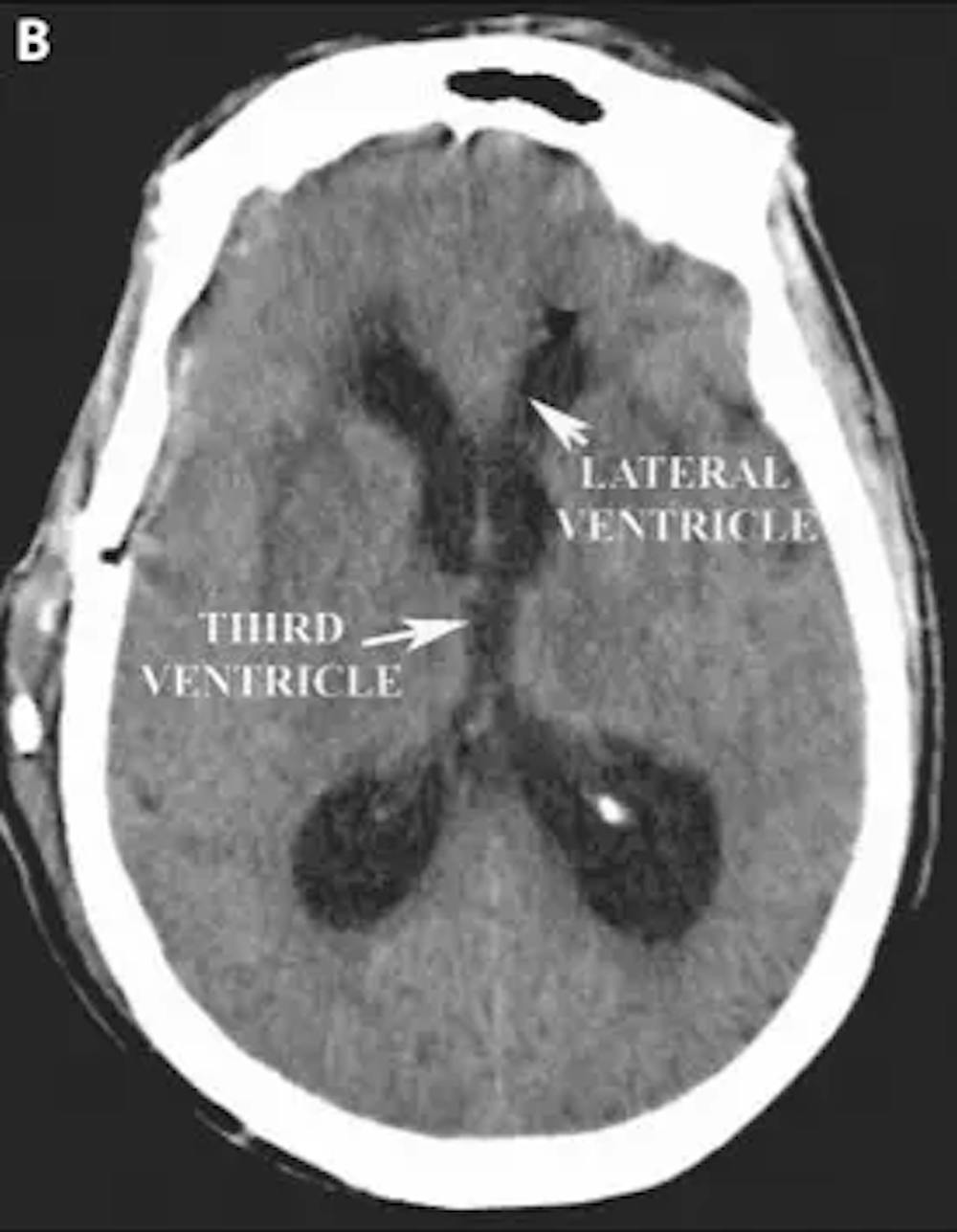

B) Post-operative axial head CT demonstrating decrease in the size of the lateral and third ventricles after shunt placement.